“The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology and the Scientific Revolution” by Professor Carolyn Merchant, an esteemed feminist ecologist at the University of California, Berkeley, provides a fascinating historical survey of the complex inter-relationship between the appreciation of women and the protection of the environment. Merchant presents a compelling argument that the Scientific Revolution, particularly from 1500-1700, led to a significant shift in our perceptions of the earth, science, and the role of women in society.

The book emphasizes how the Scientific Revolution transformed our view of the world, transitioning from an organic and nurturing motherly perspective to a mechanical and rationalized worldview. This shift, characterized by a focus on scientific laws and predictability, resulted in the devaluation of nature and the advancement of scientific methods focused on controlling and exploiting the environment.

Overall, Merchant provides a thought-provoking analysis of how the Scientific Revolution influenced our relationship with nature and led to the subjugation of women in society. Her work is both enlightening and concerning, shedding light on the historical roots of today’s ecological challenges and gender inequality. This historical perspective is crucial for understanding and addressing current environmental and gender issues.

Merchant’s book is a compelling explanation of how and why the world has reached near ecological ruin. She begins by explaining that for the life of the world before the Scientific Revolution, nature and the earth were viewed as a “nurturing mother: a kindly beneficent female who provided for the needs of humanity in an ordered, planned universe. “The metaphor of the earth as a nurturing mother gradually vanished as a dominant image as the Scientific Revolution proceeded to mechanize and to rationalize the world view.”

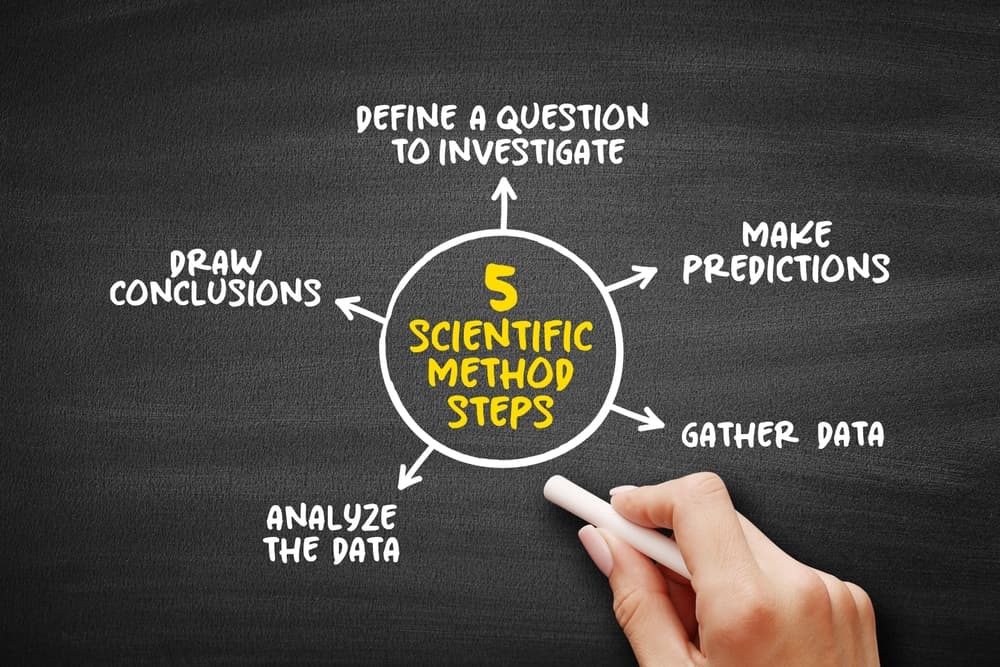

With the Scientific Revolution, a dramatic change occurred. Science began to view the world as made of components that perform according to scientific, natural laws in a predictable manner. This approach gave rise to the “scientific method” of studying the world to discover its components and the mathematical rules that controlled them. It also created a “mechanical model of society as a solution to social disorder.”

Viewing the world as a great machine system had the effect of killing the role of nature. God was nothing more than “a clockmaker and an engineer constructing and directing the world from outside.” In this conceptual framework, scientists are the real problem solvers who analyze the world and separate it “into parts that can be manipulated by mathematics.” Ergo, the title “The Death of Nature.”

Thinking of the world as a gigantic mechanical system or intricate clock provided a justification for managing, controlling, and exploiting nature. As a result, no one thought anything was wrong with industry strip mining the earth, clear-cutting forests, and draining marshes.

One of Merchant’s examples is the work of Dutch engineers in formulating and implementing comprehensive drainage plans, building dikes, and improving windmills, and the “draining of the English fens during the seventeenth century provides a striking example of the effects of early capitalist agriculture on ecology and the poor.” As draining occurred in England, the fens no longer provided fish and fowl for people living in poverty in the region. A 17th-century pamphlet reported that the fen drainage projects had a significant effect on “the faces of thousands of poor people” and “instead of helping the general poor . . . would undo them and make those that are already rich far richer.” That outcome is a perfect example of the process of social change that came with the Scientific Revolution.

Before the Scientific Revolution, the “earth was considered to be alive and sensitive,” and destroying this source of life was a breach of human values. “As Western culture became increasingly mechanized in the 1600s, the female earth and virgin earth spirit were subdued by the machine.”

At the same time, the role of women, their jobs in society, and how they were appreciated in society, as noted in literature and art, all changed. That is the compelling truth of her thesis.

Instead of being viewed as vibrant, equal partners in the “organic” blossoming of life, women began to be confined to secondary roles and to be viewed as unimportant and not an essential part of the “modern” community run by men who were in control as engineers, scientists, and technical mechanics.

Professor Merchant’s explanation of how women lost their traditional roles as midwives as a result of the Scientific Revolution most evidently demonstrates the subjugation of women that followed the Scientific Revolution.

Historically, midwives, who were often the primary caregivers during childbirth, played a significant role in society. The book meticulously documents the changes in societal attitudes and the legal battles that ensued between midwives and the male-dominated medical establishment, based on a study of court records and the litigation between the midwives and members of the Royal College of Physicians. The history is well documented. Before the 1600s, “midwifery was the exclusive province of women,” even to the extent that men were not allowed to be present when infants were born. “Midwives were professionals, usually well trained through apprenticeship and well paid for their services to both rural and urban, rich and poor women.”

With the Scientific Revolution, men who had studied medicine [at universities that barred women] were being licensed as surgeons and were seeking to practice midwifery with forceps. To prevent doctors from controlling the licensing of midwives, in a court petition, the midwives stated that Dr. Chamberlane, the inventor of the forceps for birth delivery, “hath no experience in [midwifery] but by reading . . . Further, Dr. Chamberlane’s work and the work belonging to midwives are contrary one to the other, for he delivers none without the use of instruments by extraordinary violence in desperate occasions, which women never practiced nor desired, for they have neither parts nor hands for that art.”

In addition, the famous scientist William Harvey, who discovered blood circulation, was highly critical of midwives in his writings. As a leader of the Royal College of Physicians, he was “responsible for enforcing the College’s monopoly over licensing laws.” Other male physicians were also critical, but as Professor Merchant notes: “Since most historical accounts of midwifery in this period are based on the data supplied by male writers and male midwives – some of whom, like the Chamberlane, had political motives – an accurate assessment of the state of midwifery as a woman’s art is difficult to make.” As a result, men took over advancing medical knowledge and by the end of the 1600s “childbirth was passing into the hands of male doctors and ‘man-midwives.'”

Throughout history, women have provided expertise in the delivery of babies, but in the comparatively brief period from 1634 to 1700, thousands of years of custom and tradition came to an end in England.

As a result of the Scientific Revolution and the development of medicine as a licensed profession, all women were denied the right to choose whether to have their child delivered by a male doctor or a midwife. Before the opening of medical schools to women “women had no opportunity to compare the effectiveness of the older, shared traditions of midwifery as an art with the new medical science.”

Merchant’s position is that today, ecology has taught us that the world is a connected whole. “All parts are dependent on one another and mutually affect each other and the whole.” In addition, because every part of an ecosystem is an essential part of the overall system: “All living things, as integral part of a viable ecosystem, thus have rights.”

As natural resources and sources of energy are depleted in the future, Merchant explains that new social styles will be adopted: “Decentralization, nonhierarchical forms of organization, recycling of wastes, simpler living styles involving less-polluting “soft” technologies, and labor-intensive rather than capital-intensive economic methods are possibilities only beginning to be explored.”

This leads to Merchant’s conclusion that “the conjunction of conservation and ecology movements with women’s rights and liberation has moved in the direction of reversing both the subjugation of nature and women.”

Merchant’s analysis and substantial supporting documentation are powerful and incontrovertible. Thank you, Professor Merchant.